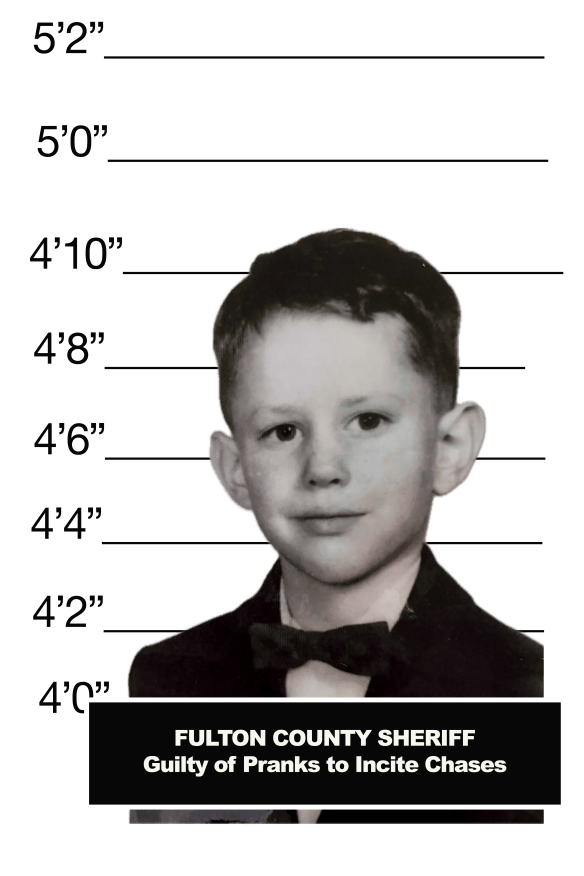

When I was in the seventh grade I switched churches for an Indian Princess, only to have true love spoiled by a freak accident in the men’s room at the Rollerama.

When I was in the seventh grade I switched churches for an Indian Princess, only to have true love spoiled by a freak accident in the men’s room at the Rollerama.

Thirty or so adolescent couples shuffled around the mahogany raised-panel room, counting out the steps to the foxtrot on the parquet floor of the old Treadwell Inn’s Colonial Ballroom. The red letters on the bass drum grandly promoted the tuxedoed trio of musicians crammed into the corner of the room as The Johnny Lanier Orchestra. The boys’ heads rhythmically bobbed up and down as they alternately studied their feet, then looked up to avoid collisions. I did my best to steer Missy Grazinski, who was actually cute in a perky, Brenda Lee sort of way. In fact, she was a local singer of some notoriety, having sung Brenda Lee’s hit song, “I’m Sorry” on the local TV variety show, Teenage Barn. The only problem with Missy was that I was at least a foot taller than her. I stepped forward trying to lead, but her backward step was too short for my long legs. My knee slid against the silky fabric of her dress and nudged a soft part of her body. I prayed it was just her leg.

“Ahh, sorry,” I mumbled, uncertain if I should acknowledge the contact or not.

Missy’s upturned face glistened under the ceiling lights of the old ballroom. “That’s okay Lucas,” she said with a big smile.

Although other seventh-grade boys might have taken her response as encouragement, I backed my legs away from Missy to avoid any further contact. After all, this was cotillion — where we were expected to learn etiquette, social graces, and ballroom dancing.

“No, no, no, no.” The excited voice from the middle of the room instantly made all the boys jumpy. I felt Mrs. Cicotti’s hand ease my outstretched butt back toward Missy. Everyone else stopped to watch.

“Are you afraid to get close to your partner?” she asked as she manipulated me into a more upright position as if I were a Gumby toy. “Here, let me demonstrate.” She took my right hand and placed it well around her own back. “The male’s right hand should be in the small of the woman’s back,” she said to everyone in the room.

I didn’t feel any smallness in the dance instructor’s back. She continued to hold my hand on her back to keep me from backing away. Her ample bosom pressed into my collarbone.

“You are bobbing your head up and down like one of those toy birds that sips out of a glass of water.” She rocked her head up and down, drawing a few nervous laughs from the crowd. “You do not have to check on your feet,” she announced, staring down to demonstrate. “Because they are not going anywhere.” I felt her swell with pride at the effect her punch line had on everyone else. But as I took in the roomful of laughing faces, I knew their laughter was mostly relief that they weren’t in my shoes.

“You should look at your partner,” she said, now smiling at me. “And carry on polite conversation.”

Her hair was pulled back tightly away from her face, exposing a row of grey roots at her scalp line. I tried not to stare at her faint mustache. At this range I could see all the fine lines in her face she had powdered over.

“I think I have it now,” I said, hoping that would be enough for her to release me.

“Yes, like this,” she said, standing up straight. “Not like this.” She bent at the waist sticking out her bum, mocking me. All the boys and even some of the girls in the class laughed.

The drummer popped his snare drum emphatically to signify it was the end of the song and time for their break. The band retired upstairs to the bar while the boys in the class retreated to the punch bowl.

“Man, she had you in her death grip,” Dondi said to me.

“You’re lucky you didn’t get your eye put out with one of her knockers,” Woody said.

Mrs. Cicotti clapped her hands together rapidly to hurry us up. “Boys, boys, you’re supposed to be offering refreshments to your partners.” She gestured to the girls sitting patiently in their fluffy dresses on metal folding chairs on the opposite side of the room. “And don’t forget the stimulating conversation,” she whispered.

Dutifully, I made my way across the room toward Missy. “Here, I brought you some punch and cookies,” I said, holding them out to her.

“Thanks, Lucas.” She beamed her usual, upbeat smile.

“Sorry I got us singled out,” I apologized. “That was pretty embarrassing, huh?”

“Don’t worry about it, Lucas.”

The seats on either side of her were taken, so I continued standing. I wondered if I should drop down on one knee to be at her level, but shook that idea out of my head. “Well, I better get going,” I said tilting my head back in the direction of the punch bowl.

“Okay, see you later.”

“Yeah, see you later.”

Terry Webb was seated next to the punch bowl with at least a dozen empty glasses scattered in front of him. He was a big kid with droopy, basset hound eyes. He always put on a terrific show of pretending to get drunk on the punch. He claimed he perfected this act by watching his dad — who owned a big leather mill in town — drink Manhattans every night at home.

“How many is he up to?” I asked as I sidled up to Malcolm.

“He’s at twenty-two cups and acting totally bladdered,” Malcolm replied.

Terry was closing in on his record of twenty-seven cups when Mrs. Cicotti called for everyone’s attention.

“We have a special surprise tonight.” She tapped Johnny Lanier’s big silver microphone. Doink, doink, doink. The amplified noise startled her, causing her to step back into one of the Grunert twins, nearly taking her out.

Dondi leaned close to me and imitating Mrs. Cicotti’s baritone voice, whispered, “Tonight we’ll practice proper introductions.”

Mrs. Cicotti composed herself and spoke into the microphone. “For a special treat tonight, Cammie and Connie will sing several of their beautiful harmonies for us.”

I groaned to myself. The previous month I had been matched up with one of the Grunert twins as a dance partner. I never did figure out if it was Cammie or Connie, which probably didn’t help. All she wanted to talk about was The City, where her cousins lived. I tried to shift the conversation to Roger Maris who, after all, played baseball in The City. But she put on a bored expression and said she could care less about whether Roger Maris broke Babe Ruth’s home run record.

When I told this story to my friends, I said, “And then she peeled off her latex mask to reveal her true identity as one of the Twin Lizard Women from the planet Reptalia. Hypnotizing me with her flicking tongue, she forced me to listen and nod with interest as she told me how enrapturing it was to see the Flower Drum Song in The City.”

“Let me introduce Cammie and Connie — the Grunert twins — singing a cappella,” Mrs. Cicotti continued.

“Singing a what?” Malcolm whispered.

“A cappella. It means they’re going to sing without any clothes on,” Woody replied.

“Without any instruments,” Dondi corrected.

“It would be more entertaining without clothes,” Woody said.

The twins were big on peace and brotherhood songs. First they sang “Cruel War” in a sappy harmony, as if they were the ones marching off to war. Then they got everyone clapping by singing “Sloop John B.”

“We come on the sloop John B

My grandfather an’ me

Around Nassau town we did roam

Drinkin’ all night”

Terry Webb joined in that last line with the twins, belting it out. A severe look from Mrs. Cicotti cut him off.

The band finally returned from the bar red-faced and with their ties undone. As Johnny Lanier queued up “In the Mood” with a wave of his arm, Dondi said, “and a one and a two and a three,” imitating Lawrence Welk. He said it was the only other place you could hear music that corny. But we always got into the swing on that number because it was the one song all evening when we were allowed to do the jitterbug.

Cotillion must have fallen on hard times because, prior to one lesson, Mrs. Webb — who was Terry’s mom — sat everyone down to ask for names of potential new recruits. She said that if we couldn’t expand our membership, everything — the dance instruction, the polite conversation, Mrs. Cicotti, the punch, the Grunert twins — all of it would be over. It was the most thrilling win-win prospect I could imagine. Shutting down cotillion sounded pretty good; recruiting girls who were not aliens sounded even better.

Terry was the first to raise his hand.

His mom peered over her reading glasses and asked, “Terrance, would you like to nominate someone?”

“Yes, mother. Abigail Russo.”

All of us turned our attention from Terry, to his mom, just like in a tennis match. We all knew that Terry loved Abby Russo, but I couldn’t imagine her joining cotillion, even if Mrs. Webb got down on her knees and begged her.

Mrs. Webb’s pen stopped in mid-air never reaching the small spiral notebook in her hand. “Address?” she commanded, in a flat tone.

We all looked back at Terry.

“Cayadutta Street.”

Two-dozen heads swiveled back to watch Mrs. Webb’s reaction.

“Street number?” She asked.

Back to Terry.

“I don’t know the street number.” He raised his chin defiantly. “Just write it down, Mom. It’ll get there without a street number.”

Mrs. Webb pursed her lips. Most of the time she was almost attractive — at least for a mom. But the hard look she had on her face right then made her lips and jowls look like crinkled paper. She held her head up with her nose in the air as if she had detected a bad odor. It seemed like just the mention of the word Cayadutta, the creek that carried all the sewage through town, including industrial wastes and chemicals from her husband’s tannery, was enough to bring the smell of the stream right into the room.

“I’m not sure we want anyone from that part of town in cotillion,” she said. Then her jaw and neck relaxed, as if the smell had suddenly gone away, and she cheerfully asked, “What other names would you children like to nominate?”

Several others offered names. Mrs. Webb controlled the entries, not even pretending to write down the ones she deemed unworthy. Trying to sound as blasé as possible, I suggested Bethany Larson. But it came out like a question, as if I was unsure a girl by that name even existed. Truthfully, I thought she was the most beautiful girl in my entire class. She had the most perfect, unblemished skin, without a mole or freckle anywhere. When she came back to school in September each year, her legs were so tan you could see perfect white stripes on her feet where her sandals had covered the skin. In contrast, I was so pale my cousins called me “Whitey” when we got together at Lake George every summer. By the end of the summer, my skin would take on a peculiar orange hue from a distance. But at closer range, my summer color revealed itself as nothing more than a solid nebula of freckles.

I knew that everyone had something they obsessed over. Kids with acne wished their pimples would go away. Short kids wished they were taller. The skinny ones wished they were heavier, and the fat ones wished they were thin. The plain ones wished they were attractive. But I couldn’t imagine what Bethany Larson might wish for; there wasn’t anything about her I would change.

When signs went up around town for a Friday night record hop at the local YMCA, I figured this might be my big chance with Bethany Larson.

“Real girls,” Dondi said. “And real music.”

“Maybe I’ll sneak Joan Novenas down into the showers and get all soapy with her,” Woody confided.

“I’m about to bite me arm off,” Malcolm said, which was just his way of saying he was excited.

Yet when the big night arrived, we all wasted most of the evening Indian wrestling, singing along with the records, and reenacting personal sports heroics. As the evening was ebbing to a close, the disc jockey finally put on “Wonderland by Night” — the most romantic, sensuous slow song of the era. I screwed up my courage and headed straight for Bethany Larson. The gaggle of girls surrounding her separated as I approached. Several twittered when I offered my hand and led her out onto the dance floor.

With conversational skills honed from hours of cotillion training, I began, “What’d you do this summer? You look really tan.”

“Oh this,” she said looking down at her arms as if noticing them for the first time in her life. “I went to the Cape with my family for the last two weeks in August. What did you do?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “I just hung around. Dondi, Woody, Malcolm and I discovered an old Indian village over near Sammonsville.”

“Really?” she asked. I could not tell if she was astonished, skeptical, or ridiculing me. “How did you know it was an Indian village?” she asked.

“Oh, we collected tons of arrowheads and pottery pieces and stuff. I have a pretty cool collection. I normally charge kids to see it, but I’ll show it to you for free.”

Other couples were already out on the floor, slow dancing around us, and here we were just talking. I had no idea how to make the switch to dancing. I considered holding out my arms as an invitation, but what if she didn’t pick up on it? Then I would look like an idiot, as if I were standing in front of her with an invisible partner. So I tried flattery.

“You know, you’re so tan, you could probably pass for an Indian.” I smiled and wondered if it were possible to pay someone a better compliment. Bethany scrunched up her nose, making me wonder if her opinion of Indians differed from my own.

I needed the remainder of “Wonderland by Night” to fast talk my way out of that one. I wasn’t sure if my rambling, incoherent explanation made any more sense to her than it did to me, but I was pretty sure it contained the words Indian and Princess in the same sentence, and that may have been what kept her out on the dance floor talking to me. When the DJ announced the next song would be “The Twist” and that the night would close with a Twist contest, the place started buzzing. Here was a dance that required absolutely no skill or footwork — all you needed was athletic energy. Mrs. Webb and Mrs. Cicotti had banned the twist at cotillion, which automatically cemented it as our favorite.

The DJ announced the judge for the contest and Stanley Saco stepped onto the dance floor. Stanley was the fitness director at the Y. He reminded me of an elephant, with folds of saggy skin covering his muscular frame. Stanley told us stories of traveling the vaudeville circuit as a young man. He taught us cool things like juggling and acrobatics. His best trick was balancing kids in their bare feet on top of his bald head.

On this particular night, Stanley twisted all around the dance floor, demonstrating the proper technique to everyone. He twisted from couple to couple, holding his hand over the couples being eliminated, until only Bethany and I and one other couple remained for the final twist off. The rest of the banned dancers surrounded us, clapping in beat to the music.

I felt myself following my partner’s more practiced movements. She looked like the snake charmer and I felt like the snake. When she urged me on with the words, “Go Lucas, go!” I tried so hard it felt like I might corkscrew myself through the floor. Stanley threw feints from the other couple to us, as if changing his mind on who to eliminate. I knew it was a just routine he had picked up from the TV show To Tell the Truth. The contestants would try to fake out the audience by pretending to stand up, when Bud Collyer the host would call out, “Would the real Percy Hoskins please stand up?” Stanley may have kept everyone else in suspense with his theatrics, but he didn’t fool me.

In the end, it was a magical evening. As we walked home, Dondi and Woody went on and on about how much they’d “gotten off of” Judy Fiorelli and Joan Novenas, slow dancing to the song “Wonderland by Night.” Dondi said that Judy had melted in his arms, but that was to be expected because he always felt he was irresistible to girls. Malcolm had successfully “chummed the waters in Dondi’s wake,” as he put it, and had an equally satisfying slow dance with one of the cast-offs.

I had never even touched my dance partner. But through my skillful conversation, she came away thinking I considered her as beautiful as an Indian princess, and together we had come in second place in the Twist contest. Walking home that evening, I felt an unfamiliar, not unpleasant nervous feeling in my belly that promised to blossom into something sweet and spectacular. The feeling lasted several more weeks. But unfortunately, that evening proved to be the high point of my relationship with Bethany Larson. With all the best intentions, somehow all future encounters would prove to be disastrous.

Soon after that evening, I switched churches for Bethany Larson. After baptizing me in the Methodist Church, my parents washed their hands of any further religious training, figuring they had done their part. They never noticed, or at least never asked, when I began getting up early on Sundays well before them, and walking six blocks to the First Presbyterian Church. If pressed, what would I have told them? I liked the sermons better? Nicer stain glass windows? I certainly wouldn’t have told them the truth. The Presbyterian Church had much cuter girls (one in particular) and they had field trips that involved long bus rides with these girls. I certainly did not tell them that I had signed up for one of these bus rides to go roller-skating several hours away.

Bethany Larson was looking out the window as I made my way down the aisle of the bus. Betsy Suttliff, who was sitting next to Bethany, gave me a knowing smile as I passed. I sat in the back of the bus daydreaming about skating hand in hand under the lit crescent moon. As I laced on my skates at the Rollerama, Betsy rolled unsteadily up to me and bent over, placing her hands on her knees for support. “She’d kill me if she knew I told you, but Beth really wants to sit with you on the ride home,” she said.

I felt the blood rushing to my face. “If I don’t kill myself on these things first,” I said, pointing to my tan and burgundy skates that looked like high-top bowling shoes on wheels.

Before going out on the rink, I found the men’s room. I balanced with the fingertips of my left hand on the wall in front of me and tried to relax. Just as my stream reached full force, some kid rolled unsteadily into the room and, when he windmilled out of control, clipped one of my skates from behind. By the time I regained my balance, I had managed to pee all over the front of my wide wale corduroys. Panic set in as I hid in a toilet stall, unsuccessfully blotting and fanning the stain. The only solution was to tie my jacket around my waist backwards. When I finally emerged from the men’s room, I cringed when I saw Bethany Larson’s reaction to this unlikely fashion statement. She looked confused, then quickly looked away in embarrassment. Every time the electric “couples only” moon lit up, I veered back into the men’s room to wait it out.

I wondered if through sheer will power I could give myself a seizure, thinking I had heard somewhere that people wet their pants when they had seizures. It might even elicit sympathy, but I decided it would be the fatal kind. So instead, I pretended I was coming down with the flu, which was exactly the way I felt anyway. I sat alone in the front of the bus during the long ride home just in case I had to get out to puke. No one wanted to sit near someone with the flu anyway.

When I was in the seventh grade I switched churches for an Indian Princess, only to have true love spoiled by a freak accident in the men’s room at the Rollerama.

When I was in the seventh grade I switched churches for an Indian Princess, only to have true love spoiled by a freak accident in the men’s room at the Rollerama.