Giddy with the anticipation of summer vacation, we walk ed home from Smalley’s Theater after watching Elvis punch his way to glory in Kid Galahad.

ed home from Smalley’s Theater after watching Elvis punch his way to glory in Kid Galahad.

Dondi careened into Malcolm harder than he needed to. In his best Elvis voice Malcolm said, “Watch it Willie. I may be a grease monkey, but I don’t slide so easy.”

Dondi wrapped his arm around Malcolm’s neck and pulled him close. “I don’t slide so easy,” he said, drawling the word “slide.” “Elvis is from Memphis, not Manchester.”

“All right, all right,” Malcolm said, squirming out from underneath Dondi’s headlock. “Lucas, do the Hamburger Haven one again. You do that one the best.”

I looked over at Dondi who just shrugged. “Aw Willie,” I began, in what I felt was the best Elvis impersonation of our group. “You have got a dirty mind, haven’t you Willie? I’ll tell you what I did to your sister. I’ll tell you right to your face. We went to the Hamburger Haven and held hands on top of the table for half an hour — is that so bad, is it Willie?”

Dondi cut in, “I’ll tell you another thing Willie. I’m getting out of this fight game as soon as I can.” Dondi veered into Woody and asked, “You know why Willie?”

“I dunno,” Woody said, refusing to play along.

Dondi cut the opposite way, crashing into Malcolm. “You know why, Willie?”

Already laughing as he anticipated the punch line, Malcolm barely spit out, “No, why?”

“I’ll tell you why, Willie,” Dondi said, leaning over with his face up close to Malcolm’s. “Because it stinks.” Except he said it like Elvis, so the word came out as “Stinsh.”

High above us the black branches of the doomed elm trees reached toward each other from opposite sides of the street. No streetlights lit this stretch, making it a dreaded section after horror movies. The big colonial houses on both sides of the street loomed out of the darkness. Flickering silver light from black and white TVs danced in the windows of some of the houses. As Dondi completed his Elvis delivery, a motion on Miss Myron’s front porch caught my eye. A silhouette rocked silently, taking in the cool night air.

Ethel Myron was our spinster school librarian. You would think that someone who was forever telling us to stop talking would be less of a town gossip. I imagined her telling her neighbors over coffee, “They sounded like southerners, shouting and picking fights with each other. One accused the other of doing Lord knows what with the other one’s sister!”

Fortunately, we were well past Miss Myron’s house when Woody brought up the kissing scenes in the movie. “They were sucking tongues like there was no tomorrow,” he said.

“It was disgusting,” Malcolm said. He made a face and drooled a long hank of spit onto the sidewalk. “Swapping spit with a girl.”

“I’d do it in a minute,” Dondi said.

“Me too,” said Woody.

That’s when Malcolm divulged the amazing anatomical secret that girls have nuts in their breasts. His only proof was Sally Schultz’s reaction to getting drilled in the chest with a hardball during a neighborhood baseball game.

“Remember? She was doubled over just like she’d been kicked in the goolies,” he said. He grabbed his right breast and staggered as if he’d been shot. “Except she got hit right in the baps.”

“What’s that prove? Sally Schultz doesn’t even have boobs, anyway,” Woody said.

Whatever Malcolm lacked in scientific discovery was more than made up by the fact that he had an older sister who was in high school. That was enough credibility to cement this biological fact about girls in our minds. We walked together in silence for a full block, digesting our new knowledge.

As we ambled up the William Street hill, Malcolm finally broke the silence. “You know that Sawyer girl?”

Of course we all knew the red headed girl who was two years younger than us and lived next door to Malcolm. She always jumped rope and played hopscotch on the sidewalk. Sometimes we would find her on Malcolm’s front steps, talking to Malcolm and the other neighborhood kids.

“What about her?” Dondi asked.

“I can’t stand her,” Malcolm said.

I looked at Malcolm skeptically. “What do you have against her? She seems nice enough.”

Malcolm sighed deeply as if his list of complaints was too long to consider. “Well, for one thing, she’s as flat as a board.”

We stopped walking and stared at Malcolm.

“What the heck are you talking about? She’s only like ten years old,” Dondi said.

We were at the corner of William and First Avenue where we always split up to go our separate ways home. Woody parroted back Malcolm’s words, “I can’t stand her…she’s as flat as a board.”

Malcolm said, “Hey Dondi, do the Hamburger Haven routine one more time.”

“Aww, Willie,” Dondi began. Then he stopped.

Malcolm had walked away, in the direction of his house. He called back over his shoulder, “You have got a dirty mind, haven’t you Willie?”

That’s when we all knew the truth — that Malcolm liked the Sawyer girl.

We walked the seven blocks to Smalley’s Theater every Friday night, unless there was a night football game. When the theater jacked up their admission price from twenty-five to thirty-five cents, Malcolm declared it the biggest gyp joint in town. His boycott gained support from the rest of us for six days. But when the following Friday rolled around, our resolve crumbled. Smalley’s was just too magical to resist.

The theater looked tiny from the outside, but it was cavernous inside with hundreds of plush, red velvet seats. Originally built for the vaudeville circuit, its art deco fixtures were as exotic and far-fetched as the images flickering on the big screen, from movies like The Blob and The Time Machine.

The usher, a high school kid we called Paper Thin for his hair-do that was greased into a sharpened wing overhanging his forehead, patrolled the big balcony to keep kids out. More than anything, Woody wanted to sneak up there with a container of cooked oatmeal, make loud, retching noises, and dump the whole mess onto the crowd below.

“My cousin’s friend did it in the town where he lives,” Woody said as we walked home after seeing Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea.

Dondi skeptically raised one eyebrow but didn’t say anything.

“What, you don’t believe me?” Woody said. “You can call my cousin up. He’ll tell you.”

But of course Woody couldn’t produce a phone number. And even if he did, it was long distance, and we weren’t allowed to make long distance calls. So, it became part of our code that we accepted each other’s stories about far away cousins.

The most famous of these friend-of-cousin legends involved a high school girl who constructed the perfect beehive hairdo. To preserve it, she slept with her head elevated and never washed her hair. She just kept coating it with hair spray until it was entombed in a solid shellac-like coating. Eventually maggots ate through the protective coating into her brain. Here the legend mutated into two different versions, depending on whether your cousin was from upstate or downstate New York. In the upstate version, the girl tragically died from the maggots eating into her brain. In the downstate version, she became a living vegetable. Lots of famous people, who were supposed to be officially dead, like James Dean and Marilyn Monroe, were rumored to be living vegetables during this period.

The candy counter in Smalley’s Theater glowed in the darkened lobby like it was the control board of a space ship. It contained wonderfully weird stuff you couldn’t find anywhere else. There were flavored wax lips, which were a three-in-one candy. You could wear them for a while, chew the flavor out of them, and then chuck the remaining wad of wax at other kids in the theater. Or, for five cents, you could get a whole six-pack of little wax bottles, filled with colored, sugar water. Those were good for chewing and throwing too.

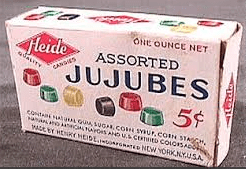

The best projectile candy hands-down was Jujubes. They tasted oddly like  soap, so you only kept them in your mouth long enough to soften up the outside. Then they would stick to almost anything they hit. These candies, which looked like the prehistoric drops of amber that trapped insects, would suck the fillings out of your teeth if you bit down on them.

soap, so you only kept them in your mouth long enough to soften up the outside. Then they would stick to almost anything they hit. These candies, which looked like the prehistoric drops of amber that trapped insects, would suck the fillings out of your teeth if you bit down on them.

Adults normally avoided Smalley’s as if it were a war zone, which on most Friday nights it was. That’s why Malcolm, Dondi, Woody, and I felt as if we were trapped behind enemy lines, as grown-ups mysteriously surrounded us before one show.

“What’s playing anyway?“ I whispered as we sat waiting in the darkened theater.

“I don’t know, but if they’re showing Children of the Damned again, these people are sure going to be disappointed,” Woody said.

As Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess lit up our faces, the woman sitting two seats to our right stared at us wearing our oversized wax lips. “You boys should be ashamed of yourselves, mocking these Negroes like that.” Dondi and Woody immediately ditched their wax lips onto the floor.

As Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess lit up our faces, the woman sitting two seats to our right stared at us wearing our oversized wax lips. “You boys should be ashamed of yourselves, mocking these Negroes like that.” Dondi and Woody immediately ditched their wax lips onto the floor.

Malcolm dropped his into his shirt pocket where his mom discovered them weeks later as she ironed. Malcolm continued to wear the shirt despite what looked like a bloodstain over his heart. “I could keep me matches in here and they’d never get wet,” he always bragged as he’d peel the pocket open.

I kept wearing my lips. I couldn’t see what all the fuss was about, especially since our chorus teacher had staged a minstrel show for the winter concert that year, painting all our faces black and having us sing songs like “Mama’s Little Baby Loves Short’nin Bread.” I felt especially bad for Anthony Jefferson. Mrs. Lippiello chose not to paint Anthony’s face black, which was embarrassing enough because it made his milk chocolate face really stand out in our sea of licorice ones. What was even worse was when Joey Kavarvic got up there on stage in blackface, and sang the lead solo to an audience of adoring white faces. All of us kids knew that Anthony had a way better voice than Joey, so it was kind of unfair that Joey got the lead solo. Still, I was thankful Mrs. Lippiello at least had enough sense not to make Anthony sing the lyrics:

“I’s a little pickaninny,

blacker den a crow.

But I’s as sweet as lasses candy,

Mammy told me so.”

Imitating the falsetto voice of the lady on the screen, Dondi softly cried out “Crawdads, craw-da-uds.”

A long, drawn out shhhhh hissed ominously from the woman directly in front of Malcolm. She flung one end of her fur wrap over her shoulder as an angry exclamation point. The wrap was the type that had an animal head attached to it. The head landed pointing backwards, staring directly at Malcolm with its beady black eyes.

Up on the screen, Porgy was singing, “Bess, you is my woman now, you is, you is! An’ you mus’ laugh an’ sing an’ dance for two instead of one.”

“What is it?” Malcolm whispered to Dondi, as he pointed at the animal head.

Dondi leaned close to Malcolm and whispered in his ear, “It’s a rabid squirrel, and if you don’t shut up, it’s going to attack your nuts.”

Malcolm gagged on his coke as he tried not to make any noise. At that moment, Paper Thin in his gold-trimmed, burgundy usher’s suit, that made him look like an escapee from the circus, appeared behind Dondi and bonked him on the head with his flashlight. Little squeaks escaped from Malcolm as he held his breath. But the laughter had to go somewhere, and like a pressure relief valve, coke exploded out of his nose, sending a mist in the direction of the fur stole lady. Her husband whirled around in his seat, pointed at us and growled at Paper Thin, “Either they go, or we go.”

As we walked home, chewing the flavoring out of our wax bottles, Woody said, “The movie wasn’t even half over. They should have at least given us twenty cents back.”

“We’re regulars. We’re the ones butterin’ their bread,” Malcolm added. “Then some squirrel-infested lady comes in one time to see some lame musical, and gets us thrown out?”

Then Dondi called out “crawdads” again, sounding like the lady in the movie, and we all doubled over in laughter.

On the night we saw the movie, Sink the Bismarck, we marched home in  unison discordantly belting out the theme song.

unison discordantly belting out the theme song.

“We’ll find that German battleship that’s makin’ such a fuss,

We gotta sink the Bismarck ‘cause the world depends on us.

Hit the decks a-runnin’ boys and spin those guns around,

When we find the Bismarck we gotta cut her down.”

To us, World War II was more than a lifetime in the past. It seemed even more distant to us because our fathers who had served in the war never discussed it. Snooping through the U.S. Army pins and ribbons in my dad’s desk one day, I discovered an amazing piece of war booty — a large dagger with a carved wooden handle. On the handle there was a silver eagle with spread wings and talons sunk into a round emblem below it. I rubbed my finger over the tiny embossed metal swastika in the middle of the emblem. Removing the decorated metal scabbard revealed a sinister, foot-long blade, oily and sharp on both edges. Engraved on one side of the blade in fancy script letters were the words, “Alles fur Deutschland.”

In the bottom of the desk drawer I found a plain manila envelope, stuffed full of photographs. Some of the photos showed railroad boxcars piled high with human bodies. The bodies appeared to be slathered with mud. In other photos, rows and rows of hundreds, maybe thousands of naked bodies lay face-up on the ground, with their eyes and mouths wide open. Their arms and legs were so thin and their ribs were sticking out so far, at first I thought they were skeletons. I returned to that drawer many times, studying each face with a magnifying glass, searching for any expression that might provide a clue of what had happened to these people. The despair captured on each face haunted me. On the outside of the envelope was the one word, “Dachau.” It was decades before I learned that my father had been one of the first into the death camp when it was liberated, which explained a lot about my dad.

As kids — perhaps because the topic was so squelched — we craved information on the war. Judging from the nearly empty theater, Sink the Bismarck’s raw, semi-documentary style with grainy, black and white footage of actual naval battles probably repelled most adults. But for us, it was mesmerizing. It traced the story of the flagship of the German Navy, which had guns with a range of over nine miles, well beyond the range of Britain’s ships. We watched in disbelief as the Bismarck sank the HMS Hood in the Battle of the Denmark Strait. The Hood was the pride of the Royal Navy. She carried 1,415 crewmen. Most of those who made it off the ship before it sank were machine-gunned in the water by German U-boats. Out of the entire crew, only three survived. In the dark, Malcolm whispered to us that his father had known some of the guys who died on the Hood.

When Winston Churchill issued the order in the film to “sink the Bismarck at all costs” we were ready to volunteer on the spot. The movie then wasted a lot of time with the British Navy cruising around, trying to locate the Bismarck, which we all agreed was the most boring part of the whole movie. But when the Brits finally located her and damaged the ship’s rudder with torpedoes dropped from airplanes, we started screaming and hollering and slapping each other on the back. When the Bismarck finally went under, we fell silent.

When The Great Escape arrived at Smalley’s Theater, we all agreed it was the best movie ever made. We didn’t goof around and throw Jujubes on this night. We stared silently, mouths agape, as Steve McQueen, James Garner, James Coburn, Charles Bronson, and David McCullum outwitted the Germans at every turn. The captive soldiers dug a secret tunnel, with the goal of freeing several hundred prisoners.

When The Great Escape arrived at Smalley’s Theater, we all agreed it was the best movie ever made. We didn’t goof around and throw Jujubes on this night. We stared silently, mouths agape, as Steve McQueen, James Garner, James Coburn, Charles Bronson, and David McCullum outwitted the Germans at every turn. The captive soldiers dug a secret tunnel, with the goal of freeing several hundred prisoners.

For weeks after The Great Escape, we were obsessed with digging a tunnel somewhere, anywhere. We eventually settled on tunneling out from under the lattice-enclosed front porch of my house. We chose a spot at the farthest end of the porch from the access door, figuring this would be the least likely place to be discovered. We planned to dig down vertically, take a ninety-degree turn, and then head toward my side yard. There we would excavate out an area for an underground clubhouse.

Whenever my parents left to play golf, I called Dondi, Malcolm, and Woody to come over to work on the tunnel. We developed a system using one person to dig the hole and another to load up my red Radio Flyer wagon. A third person dragged the wagon over to the access door with a rope. In the movie, the prisoners filled their pockets with dirt, and dumped it, one pocketful at a time, in the prison courtyard. At first, Malcolm insisted we deposit the dirt in my mother’s perennial garden next to our garage in the same manner.

“It’s too slow. Besides, I’ve always got dirt in my pockets,” Woody said.

“Steve McQueen never complained about that,” Malcolm said. “What’s the point of doing this if we don’t stay true to the movie?”

“Then why don’t we string up some barbed wire around my backyard while we’re at it?” I said. “That’d be more realistic, too.”

“And we could bring in some guards with Tommy guns,” Dondi added.

“If you guys just want it to be easy, why don’t we just hire a backhoe?” Malcolm said, throwing his shovel down in disgust.

“The difference is the guys in the movie had months to work and we’ve just got the time it takes Lucas’ parents to play nine holes,” Woody pointed out.

Finally we decided to shortcut the principles of the movie on this one technicality, and roll full wagonloads of dirt around to the back of the garage and dump it there. We dug a three-foot diameter hole six feet down, using a stepladder to get into it. We began striking out horizontally, but only got a few feet before losing interest in the project forever.

Years later when our tunnel was long forgotten, my father came into the house one Saturday morning, looking pale and agitated. He had been stowing some lumber under the porch when he ventured into the deepest bowels of the space and discovered the remains of our Great Escape diggings.

Now, if a thousand fathers made such a discovery, it’s unlikely that any would jump to the conclusion that their son and his friends had been trying to tunnel out from underneath the front porch. Some, like my father, might fear foul play.

As much as I wanted to ease my dad’s worries, I couldn’t help thinking that if I told him the truth he might get even more worried — about me. So, instead of confessing, I watched with interest as two of Johnstown’s finest arrived, and after cordoning off the crime scene, duck-walked under the porch. They came back out with their dark blue uniforms and glossy black shoes covered with a dust the consistency and color of chocolate cake mix. They announced with authority that the digging under the porch was a test hole dating back to when the house was built, over sixty years prior. This news was a relief to my father, who reasoned that a body buried under his front porch would put a real damper on the resale value of the house.

rdered from the soda fountain. Gleaming silver hand pumps, lined up like toy soldiers behind the counter, squirted thick, sweet syrups in all flavors — Coca-Cola, 7-Up, Pepsi, root beer, cherry, chocolate, strawberry, vanilla, and grape. We were forever experimenting with new flavor combinations. For several weeks Malcolm tried to convince us that Chocolate 7-Up would soon sweep the country. I told him it tasted like dirt.

rdered from the soda fountain. Gleaming silver hand pumps, lined up like toy soldiers behind the counter, squirted thick, sweet syrups in all flavors — Coca-Cola, 7-Up, Pepsi, root beer, cherry, chocolate, strawberry, vanilla, and grape. We were forever experimenting with new flavor combinations. For several weeks Malcolm tried to convince us that Chocolate 7-Up would soon sweep the country. I told him it tasted like dirt.

re sent home with instructions to hide in our basements all afternoon. My friends and I were like, “Yeah, right.” Instead, we biked straight out of town to our secret Indian village on the banks of the Cayadutta.

re sent home with instructions to hide in our basements all afternoon. My friends and I were like, “Yeah, right.” Instead, we biked straight out of town to our secret Indian village on the banks of the Cayadutta. nd kids always beat us in sandlot football except for one time — thanks to this truly miraculous, admittedly crappy trick play.

nd kids always beat us in sandlot football except for one time — thanks to this truly miraculous, admittedly crappy trick play. When I was in the seventh grade I switched churches for an Indian Princess, only to have true love spoiled by a freak accident in the men’s room at the Rollerama.

When I was in the seventh grade I switched churches for an Indian Princess, only to have true love spoiled by a freak accident in the men’s room at the Rollerama.