—How a Mail Order Scam Nearly Turned Me into a

Peeping Tom in the 7th Grade.

I charged into my bedroom after school, and stopped at the sight of a small brown package propped on my pillow. I ripped open the package and a box labeled Amazing Illusory X-Ray Spex dropped into my lap.

The illustration of the man leering at a woman through his X-Ray Spex made this moment worth the six week wait. The man’s eyes bugged out, and the caption promised, “See thru clothing…blushingly funny!”

I rattled the box, which felt strangely light in weight. I pried open one end and removed an unconvincing pair of glasses with cardboard frames. I put them on and held out my hands. A blurred double edge appeared around my hands and arms. I walked around my room examining everything. If those were bones I was seeing in my fingers and arms, then my Y.A. Tittle football, my Yankees baseball, and even my arrowheads had bones inside them too.

I carefully folded up my glasses, tucked them into the back pocket of my jeans, and biked over to Knox Field. Perhaps they worked better in broad daylight. If they had looked more like real glasses, I might have watched the high school girls bouncing around on the tennis court. Instead, I parked myself out of the way on one of the benches at the top of the hill overlooking the football field.

Eventually a girl approached on the cinder path that snaked along the top of the hill. She was a ninth-grader everyone called Jacki, and she clutched a stack of books to her chest with one arm and carried a field hockey stick in her free hand. Strictly in the pursuit of scientific research, I popped on my X-Ray Spex after she passed. Daylight did nothing to improve the double image of one slightly less-heavy girl walking in lockstep, inside the real one. I took off the glasses and in a moment of spite briefly considered ripping them up. Remembering they cost me a full month’s allowance, I stowed them back in my hip pocket instead.

I forgot all about the glasses until the next day during recess. I was standing under the big pine tree off to the side of the playground when Kevin Knight snuck up behind me and pulled the glasses out of my pocket.

“Cool. 3-D glasses. Where’d you get these?” Kevin asked as he started to put them on.

“They’re not 3-D, they’re x-ray glasses,” I said, snatching them back.

“Hey, come on. Let me try ‘em.” Kevin said, reaching to get them back.

“Tell you what. I’ll sell them to you for a dollar,” I suggested, knowing he always had money from his paper route.

He took a step back, and held out his hand. “Let me try them first. If they really work I’ll pay up.”

I put on the glasses and held my hand up in front of my face. “Of course they work. I can see the bones in my hand.”

Kevin fished a dorky blue plastic change purse out of his front jeans pocket, squeezed it open and pulled out a dollar bill. “I’ll pay you if you let me try them first.”

“Yeah, right. You’ll probably take a long look at those girls over there,” I said redirecting my gaze through the glasses at the nearest circle of girls. I raised my eyebrows and opened my mouth in an attempt to mimic the leering man in the ad.

“You can’t see through their clothes,” Kevin said, shaking his head.

“It’s blushingly funny,” I laughed, stealing the line that had hooked me.

“Lucas,” Kevin whispered urgently. “Let me try them on and I’ll tell you an amazing secret.”

“Why are you whispering?” I whispered back.

“It’s about Mrs. Delancey,” he said even more softly.

I removed the X-Ray glasses and stared at him. Nancy Delancey, the divorcee who lived at the top of my street, was a legend in the neighborhood. Some referred to her as Fancy Nancy because of her revealing short shorts and halter tops. The gossipers claimed she sunbathed nude. The only proof seemed to be that she had an eight-foot high fence around her backyard. I sometimes overheard snippets of conversation from mothers in the neighborhood.

The joke was that on the sunniest weekend days, Mrs. Delancey’s male neighbors became uncharacteristically industrious, climbing ladders to clean gutters, wash windows, and fiddle with the roof shingles on their houses.

I leaned toward Kevin so our faces were close and asked, “Okay, what’s your secret?”

“Promise you’ll let me try your glasses if I tell you?”

“Promise.”

“And you won’t tell anyone?”

“Okay, okay. What’s the big deal?”

He inhaled and puffed out his cheeks as he held his breath, and then exhaled. “Okay, get this.” He took a step closer to me. “You know how I have a paper route, right?”

“Yeah, I know.”

“Well, Mrs. Delancey is on my route,” he continued.

“So?”

“So last week when I went to collect, I think I kind of surprised her when I came to her door.”

“Surprised her how?”

“Well I rang the doorbell and nobody answered. So I was standing there playing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” on the buzzer. I figured no one was home.”

“Okay, okay, what happened?”

“I was about to leave, when suddenly the door opened and there was Mrs. Delancey standing in her full glory, if you know what I mean.”

I stared at him wide-eyed. “You mean…?”

Kevin urgently nodded his head yes, as if afraid to say it out loud.

“She wasn’t wearing anything?” I studied him for some sign of agreement.

Kevin kept the same solemn expression on his face, but changed his up and down head motions, to side-to-side ones.

If any other kid shared such a story, I would not have believed it. But Kevin Knight did not have it in him to make up something this fantastic. He wanted to be an Eagle Scout and spent all his free time tying knots and memorizing the states in alphabetical order.

“Do you swear on Scout’s Honor that this is really true?”

Kevin held up his right hand, made the Boy Scout sign and said, “Scout’s Honor.”

I grabbed him by his shoulders and looked directly into his eyes. “You must have been right at her chest level.”

“I wasn’t going to look there,” he said, recoiling, and pulling out of my grasp.

“You mean to tell me you were face to face with the most famous knockers in town, and you didn’t even look?”

“I couldn’t just stand there and gawk,” he protested.

“When do you go back to collect for your paper route again?” I asked.

“Next Thursday,” he replied hesitantly. He took a step back. “Why?”

“Let me collect for you next week.”

“No way,” he said, crossing his arms. “I never should have told you.” He turned to walk away.

But I grabbed his arm. “Wait, take them. I held out my X-Ray Spex as a peace offering. “A deal is a deal.”

Kevin donned the x-ray glasses and studied his hands.

“Say, about what time will you be at her house to collect again?” I asked. I wondered if he didn’t hear me, or didn’t want to answer.

Kevin looked up at me through the glasses. They were so dopey-looking, I was glad I had given them away. “Why do you want to know?” he asked.

“I could just hide in the bushes across the street before you get there,” I said. Kevin’s eyebrows pulled together so tightly I thought he was going to cry. “Come on,” I said, “No one will even know I’m there.”

Ultimately, I did reveal the plan to Woody, because he was the one friend who talked about wanting to see girls naked more than anyone. But I made him promise not to tell anyone. We figured the two of us could keep ourselves hidden as well as one.

The following Thursday while walking with me along a sunny section of Colonial Avenue, Woody rolled back his sleeve and held out his hand, as if checking for rain. “It feels like a perfect day for sunbathing to me.” Then he stretched his arms over his head and faked an exaggerated yawn. “Someone could get awfully drowsy out in sunshine like this.” He sauntered ahead of me, rolling his hips from side to side, and said, “So drowsy it’d be easy to forget to put on your clothes when you went to answer the door.”

Colonial Avenue normally saw little traffic, but on this particular afternoon, every time we approached our intended hiding spot, cars appeared. We slowed our pace to try to let the cars pass, but then the drivers slowed down even more to watch us.

Woody whispered, “It’s like we’re wearing signs that say we’re Peeping Toms!”

A nervous, guilty feeling nearly paralyzed me when we finally dove into the bushes across the street from Mrs. Delancey’s house. I parted the bushes slightly to open up a good view. We were more than a half hour early. Within a couple minutes we heard footsteps coming up the sidewalk from the direction of Knox Field. I held my breath as Abs Calhoun walked by so close I could have reached out and touched him.

Like many nicknames, most kids had long forgotten the origin of this one and associated Abs with his stomach muscles, which he always showed off. But his name had originally come about because of the abscesses in his teeth. Before his dentures, he used his tongue to hide his bad front teeth when he smiled, which had the unfortunate effect of making him look crazy and mocking, when he was trying his hardest to be friendly. This led to many arguments and fights, launching Abs’ current reputation as a tough guy and a bully.

After Abs passed by, I whispered to Woody, “What’s he doing here? He never comes to this part of town.”

Before Woody could answer, Abs spun around, and headed back our way. Nearing our hiding place, he looked up and down the street several times, put his head down with his forearms protecting his face, and charged like a fullback into the hedge, landing right next to Woody.

“Am I too late?” Abs asked.

“Too late for what?” Woody asked.

“For the peep show. This is the place, right?”

Soon, three more kids approached with so little stealth I hoped they were just passing through, but they joined us in the bushes. Within fifteen minutes the bushes were swaying with boys jostling for position. When Kevin scurried up Melrose Street looking nervous, his mouth dropped when he took in the scene of at least a dozen of us overflowing the bushes.

He shook his head, as if planning to abort the mission, but a chorus of pleas bleated out from across the street, “Do it…ring the doorbell!”

Slowly, he turned to look at the house, put his finger to his lips and walked up the steps and rang the bell. This instantly silenced the crowd as everyone strained for the best view. No one inhaled until the door opened, just a crack.

Someone inside appeared to be talking to Kevin, through the barest of openings in the door. Kevin handed the bill through the opening. All eyes strained to see; it appeared to be a woman’s hand. The hand withdrew back into the house, and Kevin surveyed the ceiling of the porch as he waited.

“You think she’s going to get her pocketbook?” I whispered to Woody.

“She’ll have to open the door wider to pay him,” Woody said.

“Hey, shut the fuck up down there. Ya gonna ruin it,” came a hoarse whisper from further along in the bushes.

Suddenly someone was back at the door. The collective yearnings of a dozen junior high school boys willed Kevin to back away, so we could see inside. Magically, he stepped back and the door opened wider, revealing Mrs. Delancey in a polka-dotted mini skirt with a revealing matching halter-top. She handed Kevin her payment for the newspaper. Then, as Kevin descended the front steps, Mrs. Delancey looked across the street, and blew a kiss. Then she spun around, causing her skirt to flare out just like Marilyn Monroe’s, stepped back into the house, and softly shut the door.

man didn’t come tap dancing out of the shadows of some past lifetime trauma; he threatened me from the future. I knew he would surprise me with a light tap on my shoulder. Turning to see who was there, my eyeballs would melt out of my skull by the flash of a thermonuclear blast.

man didn’t come tap dancing out of the shadows of some past lifetime trauma; he threatened me from the future. I knew he would surprise me with a light tap on my shoulder. Turning to see who was there, my eyeballs would melt out of my skull by the flash of a thermonuclear blast.

like I’m eight years old again, staring down Melcher Street hill in my Radio Flyer Wagon…

like I’m eight years old again, staring down Melcher Street hill in my Radio Flyer Wagon… Rock breaks Scissors, what defeats a Switchblade pulled on you by the school bully?

Rock breaks Scissors, what defeats a Switchblade pulled on you by the school bully?

unfortunately sucked at chin-ups. Four or five honest pull-ups were my limit, with one more leg-pumping, neck-stretching cheater thrown in at the end. But my salvation was the 600-yard run.

unfortunately sucked at chin-ups. Four or five honest pull-ups were my limit, with one more leg-pumping, neck-stretching cheater thrown in at the end. But my salvation was the 600-yard run.

ed home from Smalley’s Theater after watching Elvis punch his way to glory in Kid Galahad.

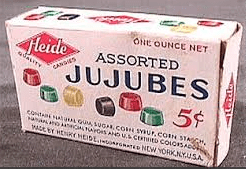

ed home from Smalley’s Theater after watching Elvis punch his way to glory in Kid Galahad. soap, so you only kept them in your mouth long enough to soften up the outside. Then they would stick to almost anything they hit. These candies, which looked like the prehistoric drops of amber that trapped insects, would suck the fillings out of your teeth if you bit down on them.

soap, so you only kept them in your mouth long enough to soften up the outside. Then they would stick to almost anything they hit. These candies, which looked like the prehistoric drops of amber that trapped insects, would suck the fillings out of your teeth if you bit down on them. As Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess lit up our faces, the woman sitting two seats to our right stared at us wearing our oversized wax lips. “You boys should be ashamed of yourselves, mocking these Negroes like that.” Dondi and Woody immediately ditched their wax lips onto the floor.

As Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess lit up our faces, the woman sitting two seats to our right stared at us wearing our oversized wax lips. “You boys should be ashamed of yourselves, mocking these Negroes like that.” Dondi and Woody immediately ditched their wax lips onto the floor. unison discordantly belting out the theme song.

unison discordantly belting out the theme song. When The Great Escape arrived at Smalley’s Theater, we all agreed it was the best movie ever made. We didn’t goof around and throw Jujubes on this night. We stared silently, mouths agape, as Steve McQueen, James Garner, James Coburn, Charles Bronson, and David McCullum outwitted the Germans at every turn. The captive soldiers dug a secret tunnel, with the goal of freeing several hundred prisoners.

When The Great Escape arrived at Smalley’s Theater, we all agreed it was the best movie ever made. We didn’t goof around and throw Jujubes on this night. We stared silently, mouths agape, as Steve McQueen, James Garner, James Coburn, Charles Bronson, and David McCullum outwitted the Germans at every turn. The captive soldiers dug a secret tunnel, with the goal of freeing several hundred prisoners.

rdered from the soda fountain. Gleaming silver hand pumps, lined up like toy soldiers behind the counter, squirted thick, sweet syrups in all flavors — Coca-Cola, 7-Up, Pepsi, root beer, cherry, chocolate, strawberry, vanilla, and grape. We were forever experimenting with new flavor combinations. For several weeks Malcolm tried to convince us that Chocolate 7-Up would soon sweep the country. I told him it tasted like dirt.

rdered from the soda fountain. Gleaming silver hand pumps, lined up like toy soldiers behind the counter, squirted thick, sweet syrups in all flavors — Coca-Cola, 7-Up, Pepsi, root beer, cherry, chocolate, strawberry, vanilla, and grape. We were forever experimenting with new flavor combinations. For several weeks Malcolm tried to convince us that Chocolate 7-Up would soon sweep the country. I told him it tasted like dirt.

re sent home with instructions to hide in our basements all afternoon. My friends and I were like, “Yeah, right.” Instead, we biked straight out of town to our secret Indian village on the banks of the Cayadutta.

re sent home with instructions to hide in our basements all afternoon. My friends and I were like, “Yeah, right.” Instead, we biked straight out of town to our secret Indian village on the banks of the Cayadutta. nd kids always beat us in sandlot football except for one time — thanks to this truly miraculous, admittedly crappy trick play.

nd kids always beat us in sandlot football except for one time — thanks to this truly miraculous, admittedly crappy trick play. When I was in the seventh grade I switched churches for an Indian Princess, only to have true love spoiled by a freak accident in the men’s room at the Rollerama.

When I was in the seventh grade I switched churches for an Indian Princess, only to have true love spoiled by a freak accident in the men’s room at the Rollerama.