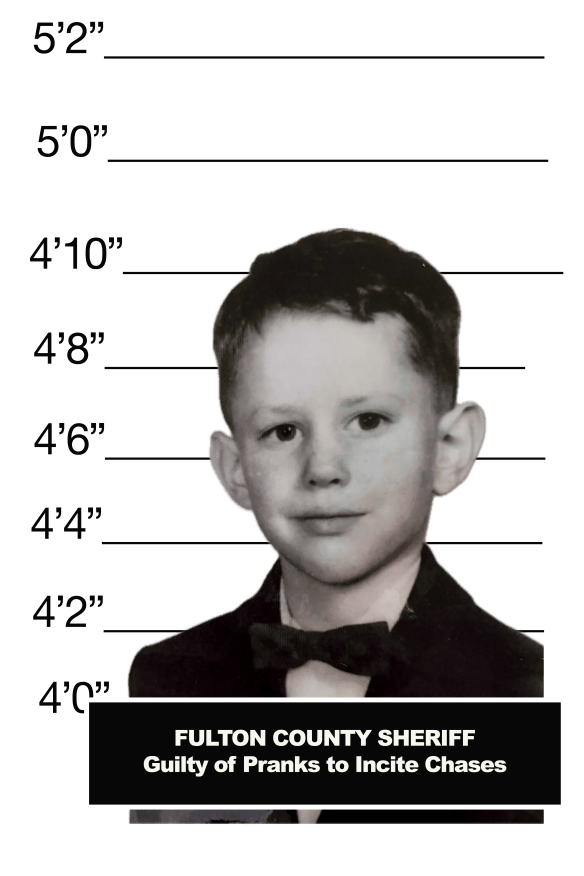

Much of the fun growing up in our sleepy mill town involved inciting people to chase after us, as in the adrenaline-inducing, dangerous kind of chase. The kind where if you’re caught, you’re dead.

The Rope Trick was our gateway prank. It required no materials and not much planning…just boredom, a dark street, and a passing car.

We usually worked the straightaway section of West Madison Ave, because drivers tended to speed up there. And all the cars back then — the Chevy Impalas and Biscaynes, the Ford Galaxies, and the Mercury Montereys — were big boats that couldn’t exactly stop on a dime.

Just two of us could pull off the trick, but it worked better with more—half on each side of the road—in a spot away from streetlamps. As cars approached, we would pretend to stretch a rope across the street.

Most drivers just tapped their brakes in surprise, but occasionally one would screech to a stop. That’s when we would scatter, racing down pitch-black driveways and backyards, relying on our superior athleticism, guile, and home-field advantage.

In our minds, we weren’t ten-year-old kids running from motorists. We were American Revolutionaries outsmarting the British. We were The Swamp Fox. We were French Resistance fighters in WWII. We were Zorro.

For all its brilliance, The Rope Trick had one major flaw. Drivers mostly sped away, annoyed. Some would crank down their window and shout out obscenities. But no one ever chased us.

So, we upped our game to something much more elaborate, using a Zebco spinning rod with an old pocketbook at the end of the line for bait.

We set up across the street from the abandoned Knox Gelatin plant at the curve on Chestnut Street. On the inside of the curve, a dense hedgerow shielded the view of the Old Ladies Home. We planted the pocketbook in the middle of the road, with a dollar bill poking out as a sweetener. Then we squeezed through the hedgerow and waited on the other side, fishing pole in hand.

It was like our own version of Candid Camera—our favorite television show. Our victims would comedically run after the pocketbook as we reeled it in. The problem again was that no one ever really chased us—except the one guy who burst through the hedgerow, sending us scattering into the darkness. But he went no further than our abandoned pocketbook, fishing pole, and dollar bill—and made off with them.

Our best setup ever for a high stakes chase ended up getting ruined by the police. It began innocently enough, when a couple of us snuck into Old Man Sweet’s backyard one night and filled up a bushel basket with apples. They were no good for eating…stealing them was payback for all the baseballs, basketballs, footballs, and wiffleballs Old Man Sweet had stolen from us over the years whenever they landed in his backyard.

We didn’t really have a plan, but as we carried the heavy basket, the wire handles were digging into our fingers. So, we set our load down in the middle of the road at the top of Melcher Street hill.

As fate would have it, at that moment a couple dozen older boys crossed Melcher Street at the bottom of the hill. High on testosterone and perhaps beer, this living unit was coursing as one, shouting, swearing, boasting, and laughing.

“Hey, you want some apples?” We shouted down at them.

The gang below us stopped, silenced.

“You big babies want some apples?”

That’s all it took for them to charge up the middle of the street toward us—an enraged, murderous mob.

We waited patiently until they were halfway up the street, then rained a barrage of apples down on them. Cries and curses erupted, and the unit broke apart, with individuals taking shelter behind the giant elms on both sides of the street.

We retreated, dragging our basket to the terraced lawn just below Stinky Mullen’s house. We made our stand there, firing apples at the kids who were steadily advancing from tree to tree. They were picking up and reusing our ammo, and they had way better arms than us.

But we knew our escape route—a path directly behind us that cut through the woods over to Hamilton Street. If we didn’t lose them in the woods, it was a short sprint to the abandoned barn on Second Avenue—always our backup plan.

Just as we were preparing to run for our lives, two squad cars roared up Melcher Street, tires crunching the apples littering the street. As the cops rounded up our attackers and tried to make sense of the scene, we slipped out the back through the woods— unnoticed, and unpursued.

______________________________________________

I’m driving in my old, but new to me, Fiat 124 Sport Coupe on Western Avenue in Albany. My front defroster and wipers can’t keep up with the snow that’s hammering down. My reaction is to lean over the steering wheel, squinting, and pressing my nose closer to the iced-up windshield.

“WAP! BAM-BAM! WAM! BAM!”

My college girlfriend flinches and yelps in surprise.

I hit the brakes, then turn into the skid I’ve caused. As the car straightens, I steal a quick glance to my right, just in time to witness another fusillade of snowballs flying out from the alley next to a bar with a neon sign, reading “Sutter’s”.

“Kids!” I announce to Kay, as I hang a right. “They’re in the alley back there.”

I turn right again into a back alley, drive halfway up the block and park. I’m guessing this is the closest I can get to them without being spotted.

I get out of the car, leave it running, and ask Kay to get behind the wheel.

“They just want someone to chase them,” I explain. “This will be fun.”

“But aren’t we going to be late for dinner?”

“If I’m not back in ten minutes, just swing around the block and pick me up out front.”

I head off into the blizzard—no hat, no gloves—retracing the route we had just driven. I want to scout out the scene, make sure they are still there, and take them by surprise.

As I approach Sutter’s on the sidewalk, there is no activity. But as I reach the front of the bar, a fresh volley of snowballs shoots out, viciously broadsiding a VW microbus.

I kneel and form two snowballs. The snow is wet and packs hard. I run into the alley—before they have time to reload.

“Okay, you guys have HAD IT!” I scream, to instill fear in their little hearts and to send them running for their lives.

Five large men stare back at me as if I am deranged. My first reaction is that I’m looking at the defensive line for the SUNY Albany football team. But these guys are way too old for that. Plus, the way they look at me, then at each other, suggests they might not be college material—maybe not even football material.

I mean, what kind of grown men stand in an alleyway during a blinding snowstorm, pelting cars with snowballs on a busy city street? Likely drunk ones who are not looking to be chased.

I fire my first snowball at the guy closest to me. He spins, turns his back, and ducks. Miraculously, my snowball strikes him with a loud smack, squarely in his butt.

His alley mates squint at me and bare their teeth, the way a Doberman Pinscher might as it’s sizing you up.

“GET HIM!” the ass-target roars.

I sprint back the way I came, my LL Bean Ranger Moccasins—which looked so cool in the catalog—offering little traction on the slick sidewalk. I turn down the first driveway to my right—five bellowing men close behind. I’m pretty sure I can outrun them.

But as I sprint down the driveway, I see a garage blocking my way at the end, and a tall chain link fence blocking both sides. There is a gate to the left which is about five feet high.

My pursuers who are halfway down the alley and breathing hard, see that I am trapped.

“You are so fucking dead asshole!” one of them shouts. The rest growl and shout murderously in agreement—too winded to form real words.

If the gate is locked, they will have me. And I’m beginning to believe that these meatheads will kill me if they can get their hands on me. So, without breaking stride, I dive headfirst over the gate, landing hard on my hands and knees.

I sprint across the backyard in which I’ve landed, wrestle my way through a cedar hedge—falling out onto the pavement of the back alley—and spot the Fiat up ahead. I race to it, jump into the passenger seat and shout, “HIT IT!”

Kay stares at my torn pants and bloodied hand.

“What? What happened?”

“Just go!” I say, rocking forward, as if that will get the car to move.

Kay looks at me, clearly annoyed.

“Listen, I’m sorry. But we really need to get going” I say, as I reach behind Kay and lock her door, then mine.

Kay puts the Fiat in gear, carefully lets out the clutch, and we slowly inch forward.

I twist in my seat to survey the alleyway behind us. There is no one. I let out a deep breath. The gate must have stopped them. I put my head back and close my eyes. My adrenaline crash, combined with the warmth of the car, makes me incredibly sleepy.

Kay navigates back to Western Ave. The snow has let up, and we still have time to get to our dinner on time.

After several minutes of driving, Kay asks, “Did you get to do your chase thing?”

“Ah, yeah,” I said, rousing from my stupor. Then with a smile, “It was amazing.”

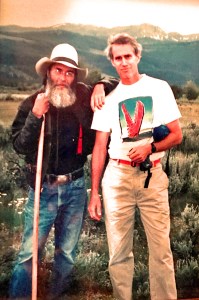

of ‘03. It was a friendly sort of kidnapping though, mostly inspired by Steve’s leukemia. What could be a better last hurrah than going to find Malcolm Howorth — who we hadn’t seen since he moved away from Johnstown when we were kids? Somehow I cajoled Dan Duross, the fourth member of our childhood gang, into joining the adventure.

of ‘03. It was a friendly sort of kidnapping though, mostly inspired by Steve’s leukemia. What could be a better last hurrah than going to find Malcolm Howorth — who we hadn’t seen since he moved away from Johnstown when we were kids? Somehow I cajoled Dan Duross, the fourth member of our childhood gang, into joining the adventure. friends.” Then he raised his glass to Sally, Sarah, and Thomas and said, “And here’s to new friends.”

friends.” Then he raised his glass to Sally, Sarah, and Thomas and said, “And here’s to new friends.”

man didn’t come tap dancing out of the shadows of some past lifetime trauma; he threatened me from the future. I knew he would surprise me with a light tap on my shoulder. Turning to see who was there, my eyeballs would melt out of my skull by the flash of a thermonuclear blast.

man didn’t come tap dancing out of the shadows of some past lifetime trauma; he threatened me from the future. I knew he would surprise me with a light tap on my shoulder. Turning to see who was there, my eyeballs would melt out of my skull by the flash of a thermonuclear blast.

like I’m eight years old again, staring down Melcher Street hill in my Radio Flyer Wagon…

like I’m eight years old again, staring down Melcher Street hill in my Radio Flyer Wagon… Rock breaks Scissors, what defeats a Switchblade pulled on you by the school bully?

Rock breaks Scissors, what defeats a Switchblade pulled on you by the school bully?

unfortunately sucked at chin-ups. Four or five honest pull-ups were my limit, with one more leg-pumping, neck-stretching cheater thrown in at the end. But my salvation was the 600-yard run.

unfortunately sucked at chin-ups. Four or five honest pull-ups were my limit, with one more leg-pumping, neck-stretching cheater thrown in at the end. But my salvation was the 600-yard run.